Have you ever wondered when exactly simulation and agent-based modelling started being widely used in science? Did it pick up straight away or was there a long lag with researchers sticking to older, more familiar methods? Did it go hand in hand with the rise of chaos theory or perhaps together with complexity science?

Since (let’s face it) googling is the primary research method nowadays, I resorted to one of google’s tools to tackle some of these questions: the Ngram viewer. If you have not come across it before, it searchers for all instances of a particular word in the billions of books that google has been kindly scanning for us. It is a handy tool for investigating long-term trends in language, science, popular culture or politics. And although some issues have been raised about its accuracy (e.g., not ALL the books ever written are in the database and there has been some issues with how well it transcribes from scans to text), biases (e.g., it is very much focused on English publications) and misuses (mostly by linguists), it is nevertheless a much better method than drawing together some anecdotal evidence or following other people’s opinions. It is also much quicker.

So taking it with a healthy handful of salt, here are the results.

- Simulation shot up in the 1960s as if there was no tomorrow. Eyeballing it, it looks like its growth was pretty much exponential. There seems to be a correction in the 1980s and it looks like it has reached a plateau in the last two decades.

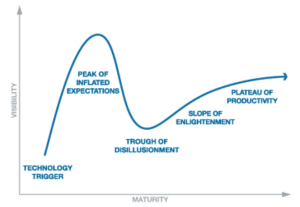

This to many looks strikingly similar to a Gartner hype cycle. The cycle plots a common pattern in life-histories of different technologies (or you can just call it a simple adaptation of Hegel/Fichte’s Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis triad).

It shows how the initial ‘hype’ quickly transforms into a phase of disillusionment and negative reactions when the new technique fails to solve all of humanity’s grand problems. This is then followed by a rebounce (‘slope of enlightenment’…) fuelled by an increase of more critical applications and a correction in the level of expectations. Finally, the technique becomes a standard tool leading to a plateau of its popularity.

It looks like simulation has reached this plateau in mid 1990s. However, I have some vague recollections that there is some underlying data problem in the Ngram Viewer for the last few years – either more recent books have been added to the google database in disproportionally higher numbers or there has been a sudden increase in online publications or something similar skews the patterns compared to previous decades [if anyone knows more about it, please comment below and I’ll amend my conclusions]. Thus, let’s call the plateau a ‘tentative plateau’ for now.

2. I wondered if simulation might have reached the ceiling of how popular any particular scientific method can be so I compared it with other prominent tools and it looks like we are, indeed, in the right ballpark.

Let’s add archaeology to the equation. Just to see how important we are and to boost our egos a bit. Or not.

3. I was also interested to see if the rise of ‘simulation’ corresponds with the birth of the chaos theory, the cybernetics or the complexity science. However, this time the picture is far from clear.

Although ‘complexity’ and ‘simulation’ follow similar trajectory, it is not particularly evident whether the trend for ‘complexity’ is not just a general increase of the use of the word in contexts different than science. This is nicely exemplified by ‘chaos’ which does not seem to gain much during the golden years of chaos theory, most likely because its general-use as a common English word would have drown any scientific trends.

4. Finally, let’s have a closer look at our favourite technique: Agent-based Modelling.

There is a considerable delay in its adoption compared to simulation as it is only in mid 1990s that ABM really starts to be visible. It also looks like Americans have been leading the way (despite their funny spelling of the word ‘modelling’). Most worryingly though, the ‘disillusionment’ correction phase does not seem to have been reached yet, which indicates that there are some turbulent interesting times ahead of us.

2 thoughts on “The hypes and downs of simulation”